| |

- 美国街道名称分类及其简称(中)

- 怪醫秦博士與油尖旺食物銀行

- 蕭神福音 之 流煮食語錄

- 北斗馬經----借賽馬九批鄧小樺

- 好書推介——《出大事了!新媒體時代的突發事件與公民行動》

- 小红猪抢稿第89期:Laptop U-Has the future of college moved online?

- Laptop U-Has the future of college moved online?

- 反摇滚的摇滚

- 蕭神福音 之《起初,蕭神創造是非》

- 明愛之恥

- 邵家臻:商討日比佔領更重要

- 【佔中十子專訪】邵家臻:佔中豈能缺社工

- 左與右

- 左與右

- 資深傳媒人批港媒日趨「假中立」 矇混新一代

- 卡斯罗和哈士奇还有小园

- 大陆城市争取赴台自由行试点

- “我们的拉萨快被毁了!救救拉萨吧!!”之波兰文、意大利文译文

- 兰心蕙性,谁为倾心?

- 大圍報編輯室手記:誰的社區?

| Posted: 17 May 2013 01:51 PM PDT 本篇的前一部分[美国街道名称分类及其简称(上)]介绍了Street、Road和Way等几个常用的街道名称类别,今天介绍的是Avenue和Boulevard。 英文Avenue和Boulevard这两个词都来源于法语,连拼写都是照搬的。它们常常是比较宽敞的道路,两旁种有观赏的树木,所以中文把它们通译为"大道"。 纽约曼哈顿市区的大部分规划得像棋盘一样,横平竖直,绝大多数东西向街道称为Street,数量有200多条,南北向的街道数量则较少,只有十来条,大多叫做Avenue,,简记为Av或Ave。比较有名的是公园大道(Park Avenue)和第五大道(Fifth Avenue)。第五大道在中城的那一段是繁华的商业区,有著名的梅西百货公司,还有全球知名品牌的旗舰店。 首都华盛顿的市政设计别具一格,市中心区也基本上是横平竖直的棋盘状,街道多称为Street。与纽约不同的是,只有南北向街道以数字命名,东西向则多半用英文字母顺序排列,字母(26个字母中的J, X-Z等舍弃不用)用完之后,就用常见的英文单词,不过仍然按照它们的首字母顺序排列,例如Belmond, Clifton等。华盛顿也有Avenue,它们比较特别,几乎都是用美国各州的名字命名,而且是从东北向西南、或从西北到东南斜穿城区。最初的设计者皮埃尔•朗方(Pierre L'Enfant)规划的这种斜街,着眼于节省交通时间,而且位于中心高地上的国会大厦可以有更加开阔的视野,市区的各个标志性建筑一览无余。100年后国会麦克米兰委员会的方案继承了这一思想。 事实上Avenue早先是一个军事用语,所以朗方的设计与这个词的内涵吻合,即在发生意外的时候便于人员紧急疏散。现在人们有时会说avenue of escape,即逃生之路,也是这个意思,例如The open window was the bird's only avenue of escape from the house等。 Boulevard原来也是军事用语,指城堡要塞高墙顶部平坦的通道,打个比方,它类似于万里长城上可以通行的走道。当人们把城墙拆掉,墙基所形成的道路自然都比较宽敞,所以被叫做Boulevard,简写为Blvd。 美国最有名的Boulevard可能要算洛杉矶的好莱坞大道(Hollywood Boulevard)和日落大道(Sunset Boulevard)了。好莱坞大道大家一定不会陌生,奥斯卡颁奖的科达剧院(现已改称杜比剧院)、许多大片首映的场所中国戏院都在那里。它还有一段人行道,地面上镶嵌着2000多块五角星形状的奖牌,用来表彰纪念那些影视音乐界的名人。每天从早到晚,去那里寻找自己喜爱的明星的人群川流不息,所以那一个路段也被叫做好莱坞星光大道(Hollywood Walk of Fame)。 日落大道从洛杉矶市中心一直延伸到太平洋海边的1号公路,全长22英里(大约35公里)。沿途经过好莱坞的那一段与好莱坞大道平行,中间只隔了一条街。日落大道还经过洛杉矶最为时尚的Westwood Village,那里的日落大厦酒店(Sunset Tower Hotel)曾经是约翰•韦恩等名人的住处。此外它所经过的比佛利山庄(Beverly Hills)和Bel Air社区,是好莱坞明星云集的高档住宅区,也是追星族旅游常去的地方。 除了这些表示宽敞的道路名称之外,还有一些通常用来表示小街小巷,例如Alley,Court,Place等,下次再作介绍。

|

| Posted: 17 May 2013 01:05 PM PDT 怪醫秦博士與油尖旺食物銀行 秦博士明白好醫生不在於有沒有註冊及完全沒有疑問地順服現存的社會制度,而在於醫者心腸及技術。同樣,好社工不在於有沒有註冊及完全沒有疑問地順服現存的社會制度,而在於易地而處的謙卑及等候朋友成長的耐性。 很多朋友是被不同的社會福利機構拒絕的死症,輾轉來到油尖旺食物銀行。有些感到憤怒,有些傷心流淚。講明是死症,我大多解決不了。但他們在我這裡一起生活,重新振作,互相幫助,勇敢地面對明天。 他們如果願意沒有保留地把自己靈魂深處的痛苦與我分享,我也會以我的靈魂分擔他們的痛苦,就算自己遍體麟傷亦在所不惜! 無條件分享食物及物資是手段,無條件分享自己及建立關係才是油尖旺食物銀行的終極目標! |

| Posted: 17 May 2013 11:12 AM PDT 流煮食語錄: 2. 人活著,不是單靠食物,乃是靠蕭神口裡所出的一切話。 3. 從來沒有在人力看見蕭神,只有在神懷裡的獨生子(即兒皇帝)將他表明出來。 4. 蕭的話是我腳前的燈,是我路上的光。 5.蕭愛兒皇帝,將自己所作的一切事指給他看,還要將比這更大的事指給他看,叫你們希奇! 影像串流: This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now |

| Posted: 17 May 2013 10:19 AM PDT 北斗馬經----借賽馬九批鄧小樺 首先,我必先要同獨媒的主編說聲不好意思,因為借了你的平台來做了一些自己心目中的行為宣示,因為這幾日的行為,我是針對鄧小樺的幼稚行為,而獨媒是出名文化人的集中地,因此我就借了這個平台,來講出文化人的劣根性。 其實馬經是一般「文化人」心目中,都是一種十分低劣的文化,如果引用鄧小樺的「指導思想」,香港賽馬停留於嬴錢嗰種,某程度上只有賭博性,只有精神慰藉成份。但我想講,就算是這樣,又如何? 香港人一般生活都已經十分勞碌,得閒死唔得閒病,星期六日跑場馬,又或者星期六日睇下鴨仔,就等同消遣一下自己的心靈。但我又覺得如何,難道每一件事都要同普選,政治,社會階層相題並論,我不是不同意鄧小姐那些理念。但是,你們這群垃圾文化人,如果睇下鴨仔可以安慰一下自己的心靈,又有甚麼問題。 香港的垃圾文化人,一直有一種通病,就是下下都把自己的思想,強加於群眾之上,例如就算食飯拉屎都要講包容,中立,普選,平等,而缺乏代入民眾的思維。記得曾經有人位前輩教導我,不是要想自己要做甚麼,而是要知道群眾想甚麼?一般垃圾文化人,他們的思想,我表示認同,但是他們會要知道群眾想要甚麼? 而這些垃圾文化人,更垃圾的是,只許州官放火,不許平姓點燈,你看看鄧小樺的反應就明白,俾人惡搞一下,立即好似別人殺了他老豆一樣,惡言相向,說甚麼言語暴力,大家看看美國總統布殊被人掟鞋,都只是笑笑口口說這是十號鞋。 最後,我想講,我只會教育民建聯支持者,為甚麼不可以投票俾民建聯。而不是屌7投俾民建聯支持者,我只會屌7民建聯的議員。 按:我會根據獨媒編輯給我的指示,寫多D有關賽馬議題的長文。 |

| Posted: 17 May 2013 09:42 AM PDT  好書推介——《出大事了!新媒體時代的突發事件與公民行動》 文:難民稻子 值得追讀的人不多,台灣那個博學的宋國誠是一個,中國的「新聞騎士」翟明磊是另外一個。 明磊的博客《壹報》自從上年六月刊出紀念六四的長詩〈招魂〉之後,便一路沉寂,我差點以為他也被失蹤了,原來是在寫書! 下面節錄他的幾條推文(翟明磊的twitter:https://twitter.com/engengpu) 「我潛心兩年半寫作的《出大事了!新媒體時代的突發事件與公民行動》已在香港上市。這兩年來,經歷了各種折騰,但我視此書為我的職責。雖曲折困苦,終於完成,這本書裡有我的勇氣與耐心。講述公民行動的策略與背後的故事,這些事件背後的真相讓人吃驚。裡面有一半的故事與推特有關。請朋友們指正。」 「寫作《出大事了:新媒體時代的突發事件與公民行動》中途,因情感與同體心的投入,難受至困頓失語,但克服心魔,終於完成。這本書,也是我的公民行動,重回推特世界,感受到消沉,但願此書重新集聚力量。以此書獻給公民社會的朋友們。 」 「——我自己還沒有讀到自己的書。勇敢地寫了,還需要有人勇敢地讀。當然還要有人能帶進來。《出大事了——新媒體時代的突發事件與公民行動》」 多講無益,我把在網上找到的陳婉瑩寫的書序貼上來,大家可以先讀: ________________ 翟明磊的新作《出大事了——新媒體時代的突發事件與公民行動》出版了,在天地書局﹑香港機場以及香港各書店銷售。 文:陳婉瑩 本書是香港大學新聞及傳媒研究中心中國傳媒研究計畫(CMP)的系列叢書,主題環繞突發事件,新媒體和群眾運動的關係,其中聚焦新媒體時代公民媒體 在突發事件中的作用和影響, 公民又如何透過媒體,挑戰社會不公、試圖改變自己的命運、激發社會變遷。書中案例反映了資訊科技動員和傳播的力量和局限,收集的案例從2003至2011 年,可以說是胡溫十年執政的一個記錄。 2003年胡錦濤和溫家寶上場, 國內外抱有厚望,期待體制改革。同年,非典爆發、大學生孫志剛在收容所的非正常死亡,考驗新政的管治能力。在非典事件中,官方始而瞞報、禁報,後來被逼放 開,顯示了面對公共衛生危機,媒體能發揮極大作用。孫志剛以生命為代價,換來中國收容遣送條例的廢除。在中國媒體史上,非典和孫案都是里程碑式的事件。 但是,以希望開始的胡溫體制下,十年來有關征地、人權、和言論自由的糾紛頻生,民眾抗爭不絕,媒體在控制和反控制之間與官方博弈,引發了連串廣受國 際關注的突發事件,本書就是這十年內最具有標誌性意義的維權事件的記錄。這包括2003年太石村村民依法要求罷免村委會主任、05年的定州因征地而引發流 血衝突、08年上海人民運用社交媒體進行磁懸浮抗爭,09年第一次通過推特多角度多方位報導和動員的番禺反垃圾焚燒場案,同年成都唐福珍為反對暴力拆遷自 焚,線民聯合抵制由政府開發、意在限制網路自由的綠壩軟體堵住資訊,壓制言論自由。郭寶峰被警方以"誹謗"之名逮捕,引發各界聲援。為規避敏感時期而被當 局要求出國的馮正虎,在世界媒體的關注和民意支持下回國。2010年調查記者揭開安元鼎截送關押訪民公司的黑幕、2011年審判代理重慶涉黑案的律師李莊 引發的微博討論等。當然,08憲章事件更長期受到國際關注,北京官方強力鎮壓,劉曉波成為了普世爭取人權和言論自由的符號。 書中的突發事件涉及不同領域,但共通之處是公民透過媒體組織維權,其中有贏有輸,比如在馮正虎回國、番禺垃圾焚燒場、綠壩事件中,正義得到伸張。在 更多的事件中,民眾失敗或慘勝,但又展示了新媒體的力量,顯示了未來的路向。在新媒體時代,人人可為記者、傳播者和出版者,公民可以透過資訊科技聯繫,動 員,為政者也必須面對新的情勢,粗暴的鎮壓只會深化矛盾,為更大的未來衝突種下禍根。 本書是新媒體,公民行動,言論自由三個圈的交集,其中行動又是核心中的核心。作者翟明磊長期橫跨傳統媒體圈,公民組織圈,新媒體博客圈,又是踐行的 公民記者。因此"行動"是全書重點。一方面,翟明磊和書中逾一半受訪者是朋友(夏霖,郭玉閃,王克勤 ,郭衛東,北風,毛向 暉,許志永,楊海鵬,老虎廟,艾曉明,艾未未,冉雲飛,斯偉江,胡佳),可以直接走進他們的內心深處,探尋他們的恐懼,失敗與勇氣;另方面,翟明磊也參與 數個案件;寫作者同時又是行動者,正是新媒體公民寫作者的特點。親身參與行動的成敗,使翟筆下的公民行動飽含感情又擊中要害,有落到實處的分析。 如馮正虎成田機場事件,翟明磊是在國內第一個發聲的公共知識份子,在成田機場事件之前,與朋友們一直關注馮正虎,並與他共同商討維權策略;在成田機 場孤寂的馮正虎在網上看到翟的支持信,這個鐵男兒竟痛哭起來。翟的文章很長時間在馮的網頁上,是唯一的支持者。在馮案中,作者也有痛苦的選擇。作為上海居 民,公開支持肯定得罪上海公安,是為大忌,翟最後忍無可忍,發出喊聲,在馮正虎回國時,親自到機場迎接。他其後迅速發表長篇馮正虎訪談《依法而行的中道力 量》兩萬字, 讓上海公安都認為文章寫得深刻。在馮案中,作者的參與使他對案例節奏、動員方法一清二楚,對當時氣氛冷暖自知。因為作者無私的幫助,馮對他坦誠交待當時種 種奧妙與自己的內心,使作者得以完成第一手的訪問。 陳光誠事件也是如此。作者是在國內最早採訪並報導陳光誠的,兩人相互支持,陳因為翟明磊認識了北京維權界的朋友們,翟的文章對陳的維權工作起了推動 作用,陳光誠也為翟的草根組織培訓學員,講述自己的案例,組織朋友們為他的計生抗爭出謀劃策。通過翟的介紹,陳認識了最後在拯救光誠事件中獨當一面地果敢 行動者郭玉閃。陳光誠後被抓坐牢,翟參與營救籌款。最後陳在駱家輝大使護送下走出使館前往醫院路上,向外界打通的第一個電話就是打給本書作者。參與使作者 的筆鋒帶有情感和無法描繪的憤怒。翟明磊回憶,陳在被軟禁期間,趁著雷電令外部手機干擾器失靈時,打通了給他的電話,沒料到就是這個電話,使陳被毆打了一 個多小時。 綠壩事件中,翟發表評論;三網友案中,他發表三篇連環評論,重火力支持。這些案例的行動者,像老虎廟,楊海鵬都是作者的好友。特別是李莊案後,他又參與了海鵬為妻子的維權案件,此案功虧一簣,使翟明磊又體會良多。 在校舍倒塌的調查案例中,作者雖然沒有參與校舍調查,但曾單槍匹馬沖到四川調查地震預報真相,最後發表有關汶川地震預報的九篇系列文章,所以對校舍調查者的處境感同身受。 此外,作者採訪已被抓的調查者譚作人的愛人王慶華,體會到她的勇氣與幽默。 楊佳案例中,作者以楊佳媽媽口述為主幹,這也是一次行動。作者說,這次口述採訪時間長達七八個小時,"通過回憶,楊佳媽媽才真實釋放了自己,我們也找到了楊佳行動最真實的原因。對楊媽媽的同情理解,這何嘗不是一次公民傾聽的行動。" 在寫作過程中, 碰上茉莉花事件。冉雲飛,艾未未被抓,作者的好友、曾救助郭寶峰的郭大蝦(郭衛東)被誣為"茉莉花組織者"被抓,作者在他被抓第二天即趕到他家,幫助他的 妻子,為她請律師。 為此作者夫婦被警方威脅訓話, 一個月沒睡過好覺,苦楚難言。後來,郭大蝦被證明是莫須有的, 作者得以分享了勝利的喜悅。 作者也是新媒體時代的先行者。翟明磊原來任職《南方週末》,離開南周後,創辦專注公民社會動態的《民間》月刊,《民間》後被封,被迫上網寫作,到網 絡維權,用網上資訊打動線民,曾在網路上開萬人公民課。當時很多人認為微博只能傳遞碎片化的資訊,但是翟用微博完整地上完兩堂五六個小時的公民課,引起反 響,成為國內微博開課的第一人,最後國務院網管局的幾個局長開會決定封了他的騰訊微博。這些實踐讓作者體會到新媒體與公民行動結合的影響力。 本書寫作的本身,就是作者的一次公民維權行動。採訪和寫作期間,作者多次受到警方干擾,甚至要求他停筆。當局後又要求少寫幾個案例、交出書稿,和要 求不要寫上海案例,這些要求被作者一再斷言拒絕,"少寫上海案例,我拒絕,磁懸浮不要寫,我拒絕。一次次談判,緊張刺激,試探底線。他們認為這本書會影響 十八大政治局,我當時大笑,'你們也太把我當回事了。'"作者回憶這些對話,歷歷在目。 翟明磊曾為CMP 撰寫《中國猛博》,該書介紹知名博客,把分散的猛博們串了起來,作者也因此和他們結識,在本書中得到了博主默契的合作。 兩年中,為探尋細節和合適的人,作者時而潛行,時而應付想不到的壓力。本書承載了作者兩年來所有的勇氣和能承擔的風險。上海警方最忌諱磁懸浮採訪, 作者悄悄進行,文中人物以水滸人物化名出現。為了和馮正虎的採訪,兩人碰頭後迅速走彎繞的地下道,拐到另一個出口談話。書中主人公們給了作者最大的"爆料 權",但是為了保護當事人,作者不得不把部分行動細節保密。 全書內容講到2011年,是對胡溫十年的盤點,其後薄熙來案發、十八大召開、新領導人上場,習近平表現親民開放,但新領導班子發出的資訊矛盾,一方 面下令改革官媒報導風格,另方面又加強網路監控。只是不管高層如何盤算 ,改革開放是不歸之路,政改已經提上日程,政治體制不改,經濟改革的瓶頸難解。 本書覆蓋的是前社交媒體時代。2012年6月中國互聯網路中心最新數字顯示,中國大陸互聯網用戶有五億三千萬,滲透(普及)率39.9%,三億八千 萬用戶通過手機上網,占線民總數的72%,有38%的線民只通過手機上網。家庭寬頻上網用戶有三億九千萬,微博在2009年出臺後,用戶量激增,三年後已 突破三億。在公民媒體時代,固有的制度受到挑戰,資訊透明成為新的標準。在這個參與者的時代。微博民眾維權的要求阻擋不了,全世界的政府和傳統組織都面對 挑戰,大學、企業,都要重新檢討、反思,接受變化成為常態的現實。進入社交媒體時代,2012年出現了薄熙來事件、網路反腐,還有7月間兩起環保維權事 件,四川什邡與江蘇啟東分別爆發上萬人特大群體抗議事件。這其中,90後的學生,通過QQ及交友網站,組織抗爭,每個事件都來得更激烈,回饋、互動更快。 在新媒體時代,為政者更要廣開言路、和民間有識之士共建開明、民主的網路文化,以面對全人類追求平等、保護環境和均衡發展等共同問題。 僅以此書獻給公民行動者,我們也相信,參與型的寫作人會秉承公民和記者的使命寫下去,為大時代記錄大事件。 |

| 小红猪抢稿第89期:Laptop U-Has the future of college moved online? Posted: 17 May 2013 08:53 AM PDT 本文作者:小红猪小分队 乔治·纳吉,一位70岁高龄的哈佛古希腊文学教授,将自己的经典课程"Concepts of the Hero in Classical Greek Civilization"搬到了网上——以时下最为火爆的MOOC形式,并得到了3万多的注册。纳吉老先生的故事,只是MOOC教育席卷世界的一个缩影,甚至包括哈佛在内的世界高校都认为MOOC将成为未来高等教育发展方向,什么是MOOC?它能为包括中国在内的发展中国家提供全新形式的教育机会吗?更重要的是,这玩意火了,和你有什么关系? 本期抢稿:Laptop U-Has the future of college moved online? 抢稿方法

P.S. 要是哪个翻译魔人(仙人、狂人、牛人)直接在48小时内搞定全篇,哼哼,那你中标的机会就大大增加啦! 抢稿须知

抢稿格式规范

|

| Laptop U-Has the future of college moved online? Posted: 17 May 2013 08:40 AM PDT 本文作者:小红猪小分队 regory Nagy, a professor of classical Greek literature at Harvard, is a gentle academic of the sort who, asked about the future, will begin speaking of Homer and the battles of the distant past. At seventy, he has owlish eyes, a flared Hungarian nose, and a tendency to gesture broadly with the flat palms of his hands. He wears the crisp white shirts and dark blazers that have replaced tweed as the raiment of the academic caste. His hair, also white, often looks manhandled by the Boston wind. Where some scholars are gnomic in style, Nagy piles his sentences high with thin-sliced exposition. ("There are about ten passages—and by passages I simply mean a selected text, and these passages are meant for close reading, and sometimes I'll be referring to these passages as texts, or focus passages, but you'll know I mean the same thing—and each one of these requires close reading!") When he speaks outside the lecture hall, he smothers friends and students with a stew of blandishment and praise. "Thank you, Wonderful Kevin!" he might say. Or: "The Great Claudia put it so well." Seen in the wild, he could be taken for an antique-shop proprietor: a man both brimming with solicitous enthusiasm and fretting that the customers are getting, maybe, just a bit too close to his prized Louis XVI chair. Nagy has published no best-sellers. He is not a regular face on TV. Since 1978, though, he has taught a class called "Concepts of the Hero in Classical Greek Civilization," and the course, a survey of poetry, tragedy, and Platonic dialogues, has made him a campus fixture. Because Nagy's zest for Homeric texts is boundless, because his lectures reflect decades of refinement, and because the course is thought to offer a soft grading curve (its nickname on campus is Heroes for Zeroes), it has traditionally filled Room 105, in Emerson Hall, one of Harvard's largest classroom spaces. Its enrollment has regularly climbed into the hundreds. This spring, however, enrollment in Nagy's course exceeds thirty-one thousand. "Concepts of the Hero," redubbed "CB22x: The Ancient Greek Hero," is one of Harvard's first massive open online courses, or MOOCs—a new type of college class based on Internet lecture videos. A MOOC is "massive" because it's designed to enroll tens of thousands of students. It's "open" because, in theory, anybody with an Internet connection can sign up. "Online" refers not just to the delivery mode but to the style of communication: much, if not all, of it is on the Web. And "course," of course, means that assessment is involved—assignments, tests, an ultimate credential. When you take MOOCs, you're expected to keep pace. Your work gets regular evaluation. In the end, you'll pass or fail or, like the vast majority of enrollees, just stop showing up. Many people think that MOOCs are the future of higher education in America. In the past two years, Harvard, M.I.T., Caltech, and the University of Texas have together pledged tens of millions of dollars to MOOC development. Many other élite schools, from U.C. Berkeley to Princeton, have similarly climbed aboard. Their stated goal is democratic reach. "I expect that there will be lots of free, or nearly free, offerings available," John L. Hennessy, the president of Stanford, explained in a recent editorial. "While the gold standard of small in-person classes led by great instructors will remain, online courses will be shown to be an effective learning environment, especially in comparison with large lecture-style courses." Some lawmakers, meanwhile, see MOOCs as a solution to overcrowding; in California, a senate bill, introduced this winter, would require the state's public colleges to give credit for approved online courses. (Eighty-five per cent of the state's community colleges currently have course waiting lists.) Following a trial run at San José State University which yielded higher-than-usual pass rates, eleven schools in the California State University system moved to incorporate MOOCs into their curricula. In addition to having their own professors teach, say, electrical engineering, these colleges may use videos by teachers at schools such as M.I.T. But MOOCs are controversial, and debate has grown louder in recent weeks. In mid-April, the faculty at Amherst voted against joining a MOOC program. Two weeks ago, the philosophy department at San José State wrote an open letter of protest to Michael J. Sandel, a Harvard professor whose flagship college course, Justice, became JusticeX, a MOOC, this spring. "There is no pedagogical problem in our department that JusticeX solves," the letter said. The philosophers worried that the course would make the San José State professor at the head of the classroom nothing more than "a glorified teaching assistant." They wrote, "The thought of the exact same social justice course being taught in various philosophy departments across the country is downright scary." Nagy has been experimenting with online add-ons to his course for years. When he began planning his MOOC, his idea was to break down his lectures into twenty-four lessons of less than an hour each. He subdivided every lesson into smaller segments, because people don't watch an hour-long discussion on their screens as they might sit through an hour of lecture. (They get distracted.) He thought about each segment as a short film, and tried to figure out how to dramatize the instruction. He says that crumbling up the course like this forced him to study his own teaching more than he had at the lectern. "I had this real revelation—I'm not saying 'epiphany,' because people use that word wrong, because an epiphany should be when a really miraculous superhuman personality appears, so this is just a revelation, not an epiphany—and I thought, My God, Greg, you've been spoiled by the system!" he says. At Harvard, big lecture courses are generally taught with help from graduate students, who lead discussion sessions and grade papers. None of that is possible at massive scales. Instead, participants in CB22x enroll in online discussion forums (like message boards). They annotate the assigned material with responses (as if in Google Docs). Rather than writing papers, they take a series of multiple-choice quizzes. Readings for the course are available online, but students old-school enough to want a paper copy can buy a seven-hundred-and-twenty-seven-page textbook that Nagy is about to publish, "The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours." Lecturing can seem a rote endeavor even at its best—so much so that one wonders why the system has survived so long. Actors, musicians, and even standup comedians record their best performances for broadcast and posterity. Why shouldn't college teachers do the same? Vladimir Nabokov, a man as uncomfortable with extemporaneity as he was enamored of the public record, once suggested that his lessons at Cornell be recorded and played each term, freeing him for other activities. The basis of a reliable education, it would seem, is quality control, not circumstance; it certainly is not a new thought that effective teaching transcends time and place. Correspondence courses cropped up in the nineteenth century. Educational radio appeared in the twenties and the thirties. The U.K.'s Open University, which used television to transmit lessons to students, enrolled its first students in 1971. The Internet was the natural next step. The University of Phoenix, for years the strongest force in for-profit online education, added a modem-dial-up support to its distance-learning program in 1989, and plans for Internet-based higher education took hold more broadly in the nineteen-nineties. At that point, the technology was shaky, and the audience was, too. Early efforts, like Western Governors University—an online school founded in 1996—saw the World Wide Web the way that many New Yorkers see Roosevelt Island: as an unexplored, accessible place with great potential of some sort, if only people understood it slightly better. In the new millennium, Harvard ran a program called Harvard@Home, initially available only to alumni. Few people watched it, though, and Harvard killed the program in 2008. Supporters of MOOCs say that they are a different and heartier species. Rather than broadcasting a professor's lectures out into the ether, to be watched or not, MOOCs are designed to insure that students are keeping up, by peppering them with comprehension and discussion tasks. And the online courses are expected to have decent production values, more "Nova" than "NewsHour." Alan Garber, the provost of Harvard and a strong advocate of online education, told me, "Long run, I see the online courses or online components becoming pervasive. Instructors in a seminar or small course might obtain modular materials from multiple sources and reassemble them in order to put together an entire course." MOOCs are also thought to offer enticing business opportunities. Last year, two major MOOC producers, Coursera and Udacity, launched as for-profit companies. Today, amid a growing constellation of online-education providers, they act as go-betweens, packaging university courses and offering them to students and other schools. Coursera, a Stanford spinoff that is currently the largest MOOC producer, serves classes from Brown, Caltech, Princeton, Stanford, and sixty-five other schools; Udacity, also the progeny of Palo Alto, focusses on tech and science. Last May, with twin pledges of thirty million dollars, Harvard and M.I.T. jointly founded edX, a nonprofit MOOC company that works with a dozen colleges and universities, including U.C. Berkeley and Rice. EdX is organized as a confederation, with each member institution maintaining sovereignty over its MOOC production; Harvard's line is called HarvardX. "This is our chance to really own it," Rob Lue, a molecular- and cellular-biology professor who leads the program, told me. For decades, élite educators were preoccupied with "faculty-to-student ratio": the best classroom was the one where everybody knew your name. Now top schools are broadcast networks. New problems result. How do you foster meaningful discussion in a class containing tens of thousands? How do you grade work? Nagy's answer—multiple-choice tests, discussion boards, annotation—is something like the standard reply, although there's lots of debate. At one extreme, edX has been developing a software tool to computer-grade essays, so that students can immediately revise their work, for use at schools that want it. Harvard may not be one of those schools. "I'm concerned about electronic approaches to grading writing," Drew Gilpin Faust, the president of the university and a former history professor, recently told me. "I think they are ill-equipped to consider irony, elegance, and . . . I don't know how you get a computer to decide if there's something there it hasn't been programmed to see." She explained, "Part of what we need to figure out as teachers and as learners is, Where does the intimacy of the face-to-face have its most powerful impact?" She talked about a MOOC to be released next academic year, called "Science & Cooking." It teaches chemistry and physics through the kitchen. "I just have this vision in my mind of people cooking all over the globe together," she said. "It's kind of nice." On campuses now, the pedagogic ideal is the "flipped classroom"—a model in which teachers preassign whatever lecture-type material is needed, as homework, and use the classroom time for peer and interactive learning. "Students, if all you're going to do is lecture at them, no longer see any reason to show up to be lectured at," Harry R. Lewis, a former dean of Harvard College, who teaches computer science, told me. "Most of our classes are video-recorded, so they'll watch the recording if your class is taught before eleven o'clock." One morning in March, I visited a meeting of what Nagy calls his "skunk works" MOOC-production team. The agenda was pressing: the next morning, CB22x was going to go live, and the videos for the first lesson were not yet finished. Natasha Bershadsky, the course's main video editor, kept checking the clock. She is not, by vocation, a Web editor: she recently defended her dissertation in Greek history, at the University of Chicago. For CB22x, she was trained in editing technique by Marlon Kuzmick, a teacher of "digital storytelling" who serves as Harvard's MOOC video guru. Nagy refers to Kuzmick as "our German director," although Kuzmick is Canadian. Nagy likes to imagine him as Fritz Lang in "Contempt," shooting a film of the Odyssey. "Marlon has authorized one of his camera people to come to Greece with me over break," Nagy told the group that morning, shifting his eyes merrily around the table. "This is a new idea." "It was very difficult to persuade her to do it," Kuzmick said dryly. "It's five days of contact time," Nagy went on. "Can you imagine Delphi, where you almost always have just the right kind of mist—and you think of that scene when Patroklos dies, where Apollo appears in a cloud of mist, and then swats the hero with the back of his hand from behind, and it's the scene that my old professor at Harvard, Cedric Whitman, said was the moment of ultimate terror, holy terror, in all of literature—and at Delphi you can see a mist like that!" Kuzmick said, "I think that we're just trying to capture moments that seem real, that seem authentic." Bershadsky showed a video segment that she had been up late cutting the previous night—a part of the online class's first lesson, setting up a concept that Nagy would use through the course. The segment started with a head shot of Nagy talking about the 1982 movie "Blade Runner." His lecture was intercut with a muted clip showing the rain-drenched death soliloquy of Roy Batty, the movie's replicant antagonist. "I've seen things you people wouldn't believe," Roy says in the movie. "Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die." Nagy spoke the crucial words and started teasing them apart. "The tears in rain are a way of comparing the microcosm of the self and the macrocosm of the rain that is enveloping the whole scene," he explained. " 'Time to die'—and, for me, a good point of comparison is the word hôrâ, which means the right time, the right place, the seasonal time, the beautiful time. Where everything comes together." The word hôrâ appeared floating in the air beside Nagy. "There's the subtitle!" he cried delightedly from across the table. In the Web lecture, Nagy talks about the scene from the Iliad in which Achilles is told of his forked destiny: "You have two choices, Achilles. Either you stay at Troy and fight, and then die young, and then get a glory that is imperishable. Or you go home. And then you don't die young. You live to a ripe old age, presumably, and you could even be happy. But you're not going to get the glory. And this glory—I use the word 'glory' to translate kleos—is not just glory. It's the glory that comes from being featured in the medium of Homeric poetry." The lesson was one of ten short ones composing the first hour of Nagy's course. Following standard MOOC wisdom, each bite-sized chunk of lecture addressed a single topic and was filmed with as much visual variety as possible: Nagy said he wanted to avoid "The Greg Show," in which students saw only his talking head. When presenting Achilles' kleos quandary, for example, he was sitting at a table with two members of his skunk-works team, Claudia Filos and Jeff Emanuel, both posing as students. They nodded as he talked. Then Filos spoke up: A little later, Nagy read me some questions that the team had devised for CB22x's first multiple-choice test: " 'What is the will of Zeus?' It says, 'a) To send the souls of heroes to Hades' "—Nagy rippled into laughter—" 'b) To cause the Iliad,' and 'c) To cause the Trojan War.' I love this. The best answer is 'b) To cause the Iliad'—Zeus' will encompasses the whole of the poem through to its end, or telos." He went on, "And then—this is where people really read into the text!—'Why will Achilles sit the war out in his shelter?' Because 'a) He has hurt feelings,' 'b) He is angry at Agamemnon,' and 'c) A goddess advised him to do so.' No one will get this." The answer is c). In Nagy's "brick-and-mortar" class, students write essays. But multiple-choice questions are almost as good as essays, Nagy said, because they spot-check participants' deeper comprehension of the text. The online testing mechanism explains the right response when students miss an answer. And it lets them see the reasoning behind the correct choice when they're right. "Even in a multiple-choice or a yes-and-no situation, you can actually induce learners to read out of the text, not into the text," Nagy explained. Thinking about that process helped him to redesign his classroom course. He added, "Our ambition is actually to make the Harvard experience now closer to the MOOC experience." When people refer to "higher education" in this country, they are talking about two systems. One is élite. It's made up of selective schools that people can apply to—schools like Harvard, and also like U.C. Santa Cruz, Northeastern, Penn State, and Kenyon. All these institutions turn most applicants away, and all pursue a common, if vague, notion of what universities are meant to strive for. When colleges appear in movies, they are verdant, tree-draped quadrangles set amid Georgian or Gothic (or Georgian-Gothic) buildings. When brochures from these schools arrive in the mail, they often look the same. Chances are, you'll find a Byronic young man reading "Cartesian Meditations" on a bench beneath an elm tree, or perhaps his romantic cousin, the New England boy of fall, a tousle-haired chap with a knapsack slung back on one shoulder. He is walking with a lovely, earnest young woman who apparently likes scarves, and probably Shelley. They are smiling. Everyone is smiling. The professors, who are wearing friendly, Rick Moranis-style glasses, smile, though they're hard at work at a large table with an eager student, sharing a splayed book and gesturing as if weighing two big, wholesome orbs of fruit. Universities are special places, we believe: gardens where chosen people escape their normal lives to cultivate the Life of the Mind. But that is not the kind of higher education most Americans know. The vast majority of people who get education beyond high school do so at community colleges and other regional and nonselective schools. Most who apply are accepted. The teachers there, not all of whom have doctorates or get research support, may seem restless and harried. Students may, too. Some attend school part time, juggling their academic work with family or full-time jobs, and so the dropout rate, and time-to-degree, runs higher than at élite institutions. Many campuses are funded on fumes, or are on thin ice with accreditation boards; there are few quadrangles involved. The coursework often prepares students for specific professions or required skills. If you want to be trained as a medical assistant, there is a track for that. If you want to learn to operate an infrared spectrometer, there is a course to show you how. This is the populist arm of higher education. It accounts for about eighty per cent of colleges in the United States. It is also under extreme strain. In the mid-nineteen-sixties, two economists, William J. Baumol and William G. Bowen, diagnosed a "cost disease" in industries like education, and the theory continues to inform thinking about pressure in the system. Usually, as wages rise within an industry, productivity does, too. But a Harvard lecture hall still holds about the same number of students it held a century ago, and the usual means of increasing efficiency—implementing advances in technology, speeding the process up, doing more at once—haven't seemed to apply when the goal is turning callow eighteen-year-olds into educated men and women. Although educators' salaries have risen (more or less) in measure with the general economy over the past hundred years, their productivity hasn't. The cost disease is thought to help explain why the price of education is on a rocket course, with no levelling in sight. Bowen spent much of the seventies and eighties as the president of Princeton, after which he joined the Mellon Foundation. In a lecture series at Stanford last year, he argued that online education may provide a cure for the disease he diagnosed almost half a century ago. If overloaded institutions diverted their students to online education, it would reduce faculty, and associated expenses. Courses would become less jammed. Best of all, the élite and populist systems of higher education would finally begin to interlock gears and run as one: the best-endowed schools in the country could give something back to their nonexclusive cousins, streamlining their own teaching in the process. Struggling schools could use the online courses in their own programs, as San José State has, giving their students the benefit of a first-rate education. Everybody wins. At Harvard, I was told, repeatedly, "A rising tide lifts all boats." Does it, though? On the one hand, if schools like Harvard and Stanford become the Starbucks and Peet's of higher education, offering sophisticated branded courses at the campus nearest you, bright students at all levels will have access. But very few of these students will ever have a chance to touch these distant shores. And touch, historically, has been a crucial part of élite education. At twenty, at Dartmouth, maybe, you're sitting in a dormitory room at 1 A.M. sharing Chinese food with two kids wearing flip-flops and Target jeans; twenty-five years later, one of those kids is running a multibillion-dollar tech company and the other is chairing a Senate subcommittee. Access to "élite education" may be more about access to the élites than about access to the classroom teaching. Bill Clinton, a lower-middle-class kid out of Arkansas, might have received an equally distinguished education if he hadn't gone to Georgetown, Oxford, and Yale, but he wouldn't have been President. Meanwhile, smaller institutions could be eclipsed, or reduced to dependencies of the standing powers. "As a country we are simply trying to support too many universities that are trying to be research institutions," Stanford's John Hennessy has argued. "Nationally we may not be able to afford as many research institutions going forward." If élite universities were to carry the research burden of the whole system, less well-funded schools could be stripped down and streamlined. Instead of having to fuel a fleet of ships, you'd fuel the strongest ones, and let them tug the other boats along. One day in February, 2012, a social scientist named Gary King visited a gray stone administrative building in Harvard Yard to give a presentation to the Board of Overseers and Harvard administrators. King, though only in his fifties, is a "university professor"—Harvard's highest academic ranking, letting him work in any school across the university. He directs the university's Institute for Quantitative Social Science, and he spoke that day about his specialty, which is gathering and analyzing data. "What's Harvard's biggest threat?" King began. He was wearing a black suit with a diagonally striped tie, and he stood a little gawkily, in a room trimmed with oil paintings and the busts of great men. "I think the biggest threat to Harvard by far is the rise of for-profit universities." The University of Phoenix, he explained, spent a hundred million dollars on research and development for teaching. Meanwhile, seventy per cent of Americans don't get a college degree. "You might say, 'Oh, that's really bad.' Or you might say, 'Oh, that's a different clientele.' But what it really is is a revenue source. It's an enormous revenue source for these private corporations." King rattled off three premises that were crucial to understanding the future of education: "social connections motivate," "teaching teaches the teacher," and "instant feedback improves learning." He'd been trying to "flip" his own classroom. He took the entire archive of the course Listserv and had it converted into a searchable database, so that students could see whether what they thought was only their "dumb question" had been asked before, and by whom. With compilation tools like this, online education turns from a dissemination method to a precious data-gathering resource. Traditionally, it has been hard to assess and compare how well different teaching approaches work. King explained that this could change online through "large-scale measurement and analysis," often known as big data. He said, "We could do this at Harvard. We could not only innovate in our own classes—which is what we're doing—but we could instrument every student, every classroom, every administrative office, every house, every recreational activity, every security officer, everything. We could basically get the information about everything that goes on here, and we could use it for the students." A giant, detailed data pool of all activity on the campus of a school like Harvard, he said, might help students resolve a lot of ambiguities in college life. "Right now, if a student wants to learn What should I do if I want to become an M.D.?—well, what do they do?" he asked. "They talk to their adviser. They talk to some previous students. They get some advice. But, instead of talking to some previous students, how about they talk to ten thousand previous students?" With enough data over a long enough period, you could crunch inputs and probabilities and tell students, with a high degree of accuracy, exactly which choices and turns to make to get where they wanted to go in life. He went on, "Every time you go to Amazon.com, you are the subject of a randomized experiment. Every time you search on Google, you are the subject of an experiment. Why not every time a student here does something?" The promise of proprietary data-gathering is appealing, because, with digital life wearing down the gates of élite universities, schools are no longer competing solely with one another; their command of the educational marketplace is being challenged by industry. A few months earlier, Faust, Harvard's president, had happened to speak with Hennessy, Stanford's president, during a congressional lobbying session in Washington. At that meeting, Faust told me, Hennessy talked about an early MOOC on artificial intelligence by one of his professors, Sebastian Thrun. The course had exploded—it ultimately gained more than a hundred and sixty thousand participants—and Thrun was not blind to the opportunity involved: he later took the MOOC from Stanford and used it to co-found Udacity with venture-capital money. When Faust returned to Boston and met with a subcommittee of deans she'd previously assembled to think about the future of education, she told me, it was with a fresh sense of urgency about needing to make online education work at Harvard. King was invited to speak at the February meeting; the Overseers asked follow-up questions that continued by e-mail and by phone during the next few weeks. Less than three months later, it was announced that Harvard and M.I.T. would launch their nonprofit MOOC-making start-up, edX. In his office that afternoon, overlooking a small quadrangle and the back of the Swedenborg Chapel, King told me that he didn't think MOOCs were quite ready to replace the classroom. "At the moment, there's a very big difference between an online experience and an in-person experience," he said. Just how much is lost has lately been a subject of debate. At Harvard, as elsewhere, MOOC designers acknowledge that the humanities pose special difficulties. When David J. Malan, who teaches Harvard's popular and demanding introduction to programming, "Computer Science 50," turned the course into a MOOC, student assessment wasn't especially difficult: the assignments are programs, and their success can be graded automatically. Not so in courses like Nagy's, which traditionally turned on essay-writing and discussion. Nagy and Michael Sandel are deploying online discussion boards to simulate classroom conversation, yet the results aren't always encouraging. "You have a group who are—they talk about Christ," Kevin McGrath, one of the coördinators of CB22x, told me soon after the discussions started up. "Or about pride. They haven't really engaged with what's going on." "Humanities have always been cheap and sciences expensive," Ian M. Miller, a graduate student who's in charge of technical production for a history MOOC intended to go live in the fall, explained. "You give humanists a little cubbyhole to put their books in, and that's basically what they need. Scientists need labs, equipment, and computers. For MOOCs, I don't want to say it's the opposite, but science courses are relatively easier to design and implement. From a computational perspective, the types of question we are asking in the humanities are orders of magnitude more complex." When three great scholars teach a poem in three ways, it isn't inefficiency. It is the premise on which all humanistic inquiry is based. Speaking with King that afternoon, I mentioned that it was especially difficult to turn humanities courses into MOOCs. King wrinkled his brow. "Why?" he asked. "Why should it be?" Evaluating student performance on massive scales can be harder when you're teaching qualitative material, I said. King disagreed: "I think assessment is probably harder in those fields to begin with—not because it's harder to assess but because it's harder to define what you wish to evaluate." Big data might help resolve this. The real potential of MOOCs, he went on, is to randomize input within a single virtual "classroom" in the way one can't in a traditional setting. "It would be possible to randomly assign different teaching methods, and different approaches, and different ways of seeing the screen, and all kinds of things," he told me. "And since the numbers are large and the potential for running many experiments is great, what you could do is completely solve, at least in an online setting, this huge problem in educational research." For the moment, data about how well MOOCs work are diffuse and scant. A cornerstone of the case for them is a randomized study that Bowen helped plan, through the Ithaka organization, a Mellon Foundation spinoff. It showed no significant difference in educational outcomes between online learning and traditional classroom learning. The MOOC in question was a statistics course, however, and a "hybrid" one: its students had a weekly in-classroom Q. & A. session. When MOOCs are a purely online experience, dropout rates are typically more than ninety per cent. "I feel as if we're very much in the experimental stage," Kathleen McCartney, a developmental psychologist and the dean of Harvard's Graduate School of Education, told me one afternoon in her offices on the edge of the old Radcliffe Yard. This summer, she'll leave Harvard to become the president of Smith. In May, 2012, when edX was announced, Alan Garber, the provost, asked her to serve on its board. "It really is a value-added question," she said. "What is the value added that a college or a university, and professional schools within the university, can offer?" Later, she got up to look for a paper that had impressed her. "This guy is a really good thinker," she said, handing me a printout of a report by Michael Barber, an adviser to the publishing and education conglomerate Pearson, with two co-authors. The paper, titled "An Avalanche Is Coming," was released this past March by the Institute for Public Policy Research, a British think tank. The avalanche in question, according to the report, is the upheaval that digital culture will bring to universities. Its authors write, "The one certainty for anyone in the path of an avalanche is that standing still is not an option." For instance, it says, Brezhnev's Soviet Union was in the path of an avalanche and didn't prepare—look what happened. Also, Lehman Brothers. The foreword was by the economist and former Harvard president Larry Summers. Written in a portentous tone and drawing heavily from the literature of tech-business strategy, "An Avalanche Is Coming" cites Richard Florida and Clayton Christensen to propose that schools take advantage of an "unbundling" in their educational responsibilities in order to remain competitive—a popular idea among MOOC supporters. "Some of the leading entrepreneurs of our times, including Mark Zuckerberg and Steve Jobs, dropped out of college to move to Silicon Valley," the report says. "Driven by the purpose of city prosperity, technology hubs could be the universities of the future." The idea is increasingly popular among a certain sector of the higher-education community. (The Minerva Project, an online-based liberal-arts university being developed with a twenty-five-million-dollar seed investment from Benchmark Capital, will have its students travel among as many as seven campuses globally, doing online-based work at each; Larry Summers chairs its board.) McCartney said, "I think it's a good paper. I got it three times yesterday." One sunny afternoon in March, the president of edX, Anant Agarwal, a fifty-three-year-old professor of electrical engineering and computer science at M.I.T., showed me around the company's new offices. EdX is two blocks from Google's Boston offices, near M.I.T.: an area of Cambridge that, in contrast to the undulating brick sidewalks and noodle-shaped streets surrounding Harvard, comes across as sleek and angular and most efficiently traversed by car. "Welcome to our start-up," Agarwal said when we shook hands. "It is very start-up-y." He gestured across the open-floorplan office, filled with ferns and stylish blond-wood furniture. Flat-screen TVs hung from the ceiling. Employees strode between workstations. "As you can see, this is what a start-up looks like," he offered one more time. Agarwal has started up a lot of start-ups, most recently one that made multicore processors. He told me that he drinks coffee, nonstop, all day. That isn't hard to believe; he walks as if in fast-forward, and when he's sitting he fidgets. In December, 2011, he launched something called MITx, under the aegis of the university, ostensibly to put his spring-semester circuits-and-electronics course online. "When we started, a sweet-spot number of students I was looking for was about ten times as many students as the M.I.T. class," he said—about fifteen hundred. "In the first few hours of posting the course, we had ten thousand students sign up, from all over the world." The course ultimately enrolled a hundred and fifty-five thousand students. Agarwal realized that he was onto something big. When the M.I.T. and Harvard brass approached him about running a MOOC partnership, he drew up a budget of sixty million dollars. At current rates, he estimates, the investment will cover edX's needs for "approximately a couple of years." He said, "As the business builds, we will see how it goes, and what we really do, what we don't do, and shuck and jive as we go along, as you might imagine in any start-up company—this is a start-up company." How edX will make money remains a little murky. Courses in the HarvardX program are now free. That will change this fall, as Harvard starts conducting what it calls "revenue experiments." MOOCs are costly to produce—Rob Lue, the HarvardX leader, told me that some courses require "in the hundreds of thousands" of dollars to get up and running—and so far there are no significant returns. The university regards its thirty-million-dollar pledge as a "venture capital" type of investment, and hopes to get its money back. One idea for generating revenue is licensing: when the California State University system, for instance, used HarvardX courses, it would pay a fee to Harvard, through edX. Another idea, geared toward the individual home user, is a basic per-course fee: you'd pay to enroll in a course you liked. There's an existing market for tuition-based online courses—the University of Phoenix, for one—and, to compete in that field, edX will have to choose its per-course price points carefully. A model often mentioned is iTunes. For the professors involved, too, the financial details remain vague. Should you get paid extra for conducting online classes? (Michael D. Smith, the dean of Harvard's Faculty of Arts and Sciences, told me that Harvard plans to start paying MOOC teachers when revenue begins flowing.) There are gnarly intellectual-property issues: if a professor launches a MOOC class at Harvard (an edX property) and then takes a job at Princeton (Coursera), who keeps the online course? Will untenured professors, who may have to find jobs elsewhere, be discouraged from MOOC-making? While nonselective institutions winnow staffs and pay licensing tithes to the élite powers, MOOCs offer substantial opportunities to academic stars, who might aspire to have their work reach a huge international audience. When Nagy decided to turn his popular class into a MOOC, he was thinking not only of its global reach—he's already working to secure CB22x inroads into Greece, India, China, and elsewhere—but of the long half-life that the course would have once it's circulating on the Web. "I could easily see a great institution like Harvard having a dynamic archive where, even after I'm gone—not just retired but let's say really gone, I mean dead—aspects of the course could interlock with later generations of teachers and researchers," Nagy told me. "Achilles himself says it in Rhapsody 9, Line 413: 'I'm going to die, but this story will be like a beautiful flower that will never wilt.' " In Cambridge, when the weather starts to warm up, fragrances return: first, there's a soft, faint scent of earth and fog; the grass comes back; and trees begin to blossom in the courtyard of the old-books library at Harvard. Groundskeepers set down mulch. On one of the first warm days of the year, I met Peter J. Burgard, a professor of German at Harvard, at the back entrance of Widener Library, where he keeps a research study separate from his office. Burgard is a tall man with a crown of wavy silver hair. That afternoon, he wore a green-and-bright-blue striped shirt, bluejeans, and lime-green socks. For all his claims to scholarly immurement, he reads a fair amount online, and speaks with a young standup comic's restless, patter-and-punch-line lilt. Unlike most tenured professors, Burgard teaches advanced German-language courses by choice, and, each summer, leads an intensive immersion program, in Munich. His other teaching is varied: his subjects include the German Enlightenment; baroque literature and art; twentieth-century art; and Goethe, Nietzsche, and Freud. Burgard is a highly regarded teacher. Since edX was announced at Harvard, though, he's been a persistent and outspoken critic of it. "I made the decision that I will not teach in HarvardX," he told me, swivelling in his chair before a large iMac. Behind it, propped on one wall, was a huge black-and-white reproduction of Gustav Klimt's "Jurisprudence," left over from a 2005 exhibition that Burgard co-curated; it depicts a man being ensnared by an octopus in front of three nude women. "To me, college education in general is sitting in a classroom with students, and preferably with few enough students that you can have real interaction, and really digging into and exploring a knotty topic—a difficult image, a fascinating text, whatever. That's what's exciting. There's a chemistry to it that simply cannot be replicated online." Burgard also worries that MOOCs may slowly smother higher education as a system. "Imagine you're at South Dakota State," he said, "and they're cash-strapped, and they say, 'Oh! There are these HarvardX courses. We'll hire an adjunct for three thousand dollars a semester, and we'll have the students watch this TV show.' Their faculty is going to dwindle very quickly. Eventually, that dwindling is going to make it to larger and less poverty-stricken universities and colleges. The fewer positions are out there, the fewer Ph.D.s get hired. The fewer Ph.D.s that get hired—well, you can see where it goes. It will probably hurt less prestigious graduate schools first, but eventually it will make it to the top graduate schools. . . . If you have a smaller graduate program, you can be assured the deans will say, 'First of all, half of our undergraduates are taking MOOCs. Second, you don't have as many graduate students. You don't need as many professors in your department of English, or your department of history, or your department of anthropology, or whatever.' And every time the faculty shrinks, of course, there are fewer fields and subfields taught. And, when fewer fields and subfields are taught, bodies of knowledge are neglected and die. You can see how everything devolves from there." I asked Michael Smith, the Harvard dean, whether he worried about the effects of MOOCs on the academic job market. "I think oftentimes this question is oversimplified," he said. "We're working very closely with our graduate school and our graduate students to think about how they can be involved in this process." Job offers today, he said, will necessarily "be different from the ones I saw when I finished up graduate school." Some Ph.D. students are being trained in MOOC production as "HarvardX fellows." Yet Burgard is not alone in his concerns. Last month, when Amherst College turned down an invitation to join edX, it was by a faculty vote of more than sixty per cent. A lot of teachers, some of whom had been browsing Harvard MOOCs, worried that they threatened to centralize higher education to an uncomfortable degree, and that their giant scale clashed with Amherst's small-class style. A single MOOC could exceed the number of alumni, dead and living, that Amherst has seen in two centuries. "I was surprised at the outcome," David W. Wills, a professor of religious history at Amherst, told me. "It seemed to come down the road as something that was going to happen." Wills started out being open to MOOCs, he said. But the more he heard the more his concerns grew, and none of edX's representatives seemed able to address them. "One of the edX people said, 'This is being sponsored by Harvard and M.I.T. They wouldn't do anything to harm higher education!' What came to my mind was some cautious financial analysts saying, about some of the financial instruments that were being rolled out in the late nineties or early two-thousands, 'This is risky stuff, isn't it?' And being told, 'Goldman Sachs is doing it; Lehman Brothers is doing it.' " The language he heard from edX, he said, was the rhetoric of tech innovation—seemingly to the exclusion of anything else—and he worried about academia falling under hierarchical thrall to a few star professors. "It's like higher education has discovered the megachurch," he told me. He and others worried about what this might do to smaller preachers. "I have to say, it turned my stomach to think that we were going to be making decisions about other people's jobs in a discussion to which they were not party," Adam Sitze, a member of the department of law, jurisprudence, and social thought at Amherst, told me. "Some very brilliant people are at institutions that are not wealthy." In a meeting, one of Sitze's colleagues, the political theorist Thomas L. Dumm, described the conveyance of MOOCs to weaker universities as "eating our seed corn." I was curious whether graduate students at Harvard, the élite professors of the future, shared any of these concerns. Most I spoke with seemed fairly sanguine about the future of a MOOC-sustained academy or, at least, upbeat in their disenchantment. "I have a hard time seeing how this makes an already dire situation for the humanities worse," Stephen Squibb, a graduate student in English, said. Might it make some things better? Peter K. Bol, a Chinese intellectual historian, started depending on computers as a graduate student at Princeton, in the late nineteen-seventies, because he was a sloppy typist. Today, as the director of Harvard's Center for Geographic Analysis, he's a leading exponent of the use of geographic-information-system technology in historical study—like Google Maps, except with a historical record's worth of information in it. To him, MOOCs look like a victory for open-access scholarship. "The question for us here was: How do you take what you're teaching to a very small group and make it accessible to a large group?" Bol told me late one morning in his office, a kind of paper jungle piled with journals, manuscripts, and books. "Unless I'm writing popular books, I'm not reaching those people. I'm not telling them stuff that I've worked hard to try to understand." Now he thinks he can. This fall, Bol will launch ChinaX, a survey of Chinese cultural history from the neolithic period to the present day. He has also launched a course to let students get involved in preparing that program. Those in "Chinese History 185: Creating ChinaX"—a campus class offered only to Harvard students—have spent this term building Bol's online course, module by module, in small groups under his direction. Teaching takes place in both a classroom and a computer lab. I sat in on one of the class meetings. Bol is a gifted teacher. When he takes the head of the classroom, his weary, slightly stiff manner falls away, as the years melt from a veteran stage actor when the curtain rises. He speaks energetically and clearly, gesturing briskly with both hands, as if making two marionettes dance. His jokes get full-classroom laughs. It was the first time I had been in an active university class since my time in college, and I fell back into old habits and a long-forgotten rhythm. I found myself taking lots of notes, college-type notes, notes more nervously dutiful and conceptual than I often take today. Once, when Bol was speaking, I glanced at my phone to see whether an important e-mail had come through. When I looked up, I found Bol's eyes on me, and flinched. I had adopted again the double consciousness of classroom students: the strange transaction of watching someone who watches back, the eagerness to emanate support. Something magical and fragile was happening here, in the room. I didn't want to be the guy to break the spell. Near the end of the two-hour session, a student raised her hand and asked Bol what he meant by a phrase he'd used, "the historian's mind-set." There were a few minutes of class left. Bol nodded and perched on the edge of a table with his legs dangling below him. A colleague and collaborator had slipped into the room, the historian Mark C. Elliott, and Bol asked him to come up to the front. The two sat side by side. Bol said, "How do I know the historian's mind-set when I see it? I know it because it's somebody interested in how things change over time, but not just that. They're also interested in the problem of how things change over time. And how to account for change over time." "I would answer it a little bit differently," Elliott said. "I would say the historian's mind-set is the person who sees what's going on, today, and assumes that whatever's happening is not happening for the first time. And that whatever we're seeing must have happened in some iteration, at some point, sometime in the past somewhere. And that those versions of the kinds of change that we see around us in various scales are just the latest installment of a very long series of similar such changes." Bol cocked his head. "So it sounds to me that you're saying—" "Here it comes!" "—that history is sort of repeating in some ways. But isn't history also cumulative—that when we see it happening a second time it's somehow different from the first time?" "Yeah, I certainly don't mean to say that it's repeating. There's a great Shirley Bassey song, actually, 'History Repeating'—" "If you could sing a bar or two—" "I'll send you the MP3. It doesn't repeat, but it rhymes." Their discussion left an energetic silence in the room, a feeling of wet paint being laid on canvas. Sitting there, I thought of similarly fragile, unexpected moments that together helped define my college education. Once, during a bout of warm midwinter weather, a teacher of Baroque chorale harmony pranced into the room and spent half of class analyzing a song lingering in his mind; the song was "June in January," and today it puts me in mind of open windows and warm Fridays. I can still see the faculty office—small, dimly lighted, chilly—where I sat as a freshman, having come with a question, as the professor, a charcoal-gray scarf looped around her neck, mentioned a document trove that became the basis for my senior thesis. I recall being in a survey-course lecture so slick and wrong-headed that, at one point, the woman sitting next to me reached over and wrote ugh-get-me-out-of-here comments in the margin of my notebook. And that she used a blue-ink Uni-ball Vision. And that the seconds while she wrote each note were bliss. I remember those moments, and I remember more. I've seen things you people wouldn't believe. Education is a curiously alchemic process. Its vicissitudes are hard to isolate. Why do some students retain what they learned in a course for years, while others lose it through the other ear over their summer breaks? Is the fact that Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg dropped out of Harvard to revolutionize the tech industry a sign that their Harvard educations worked, or that they failed? The answer matters, because the mechanism by which conveyed knowledge blooms into an education is the standard by which MOOCs will either enrich teaching in this country or deplete it. William W. Fisher III, a professor at Harvard Law School, has been experimenting with ways to split the difference. This spring, Fisher is teaching his first online course, CopyrightX, through edX. But he's also a casual student of the medium. Fisher's field is intellectual-property law—he was among those to represent Shepard Fairey and his "Hope" poster—and he works a lot on rights in the digital age. I met him one morning in his office, which had a standing desk and an ergonomic keyboard in one corner. At one point, Fisher's Portuguese water dog, Nica, wandered in. He explained to me that he has reservations about MOOCs. "Two features that can be found in most of this recent wave of online courses are: first, what could be described variously as the 'guru on the mountaintop,' or the 'broadcast model,' or the 'one-to-many model,' or the 'TV model,' " he said. Fisher has a shock of strawberry-blond hair. He was wearing a pin-striped suit and, incongruously, tan hiking boots. "The basic idea here is that an expert in the field speaks to the masses, who absorb his or her wisdom. The second feature is that, to the extent that learning requires some degree of interactivity, that interactivity is channelled into formats that require automated or right-and-wrong answers. "I think this fails to capitalize on many of the most important advantages of new technologies vis-à-vis education," Fisher said. "It's possible that it's optimal for math, computer science, and the hard natural sciences. I don't teach those things, so I'm not sure. But I'm pretty sure it's not optimal for social sciences, humanities, and law. So I wanted to try a different technique." Fisher's idea is to constrain his online course as much as possible. Online enrollment in CopyrightX was capped at five hundred students. In picking students, he looked partly for a range of ages and professions: his goal is to seed knowledge of digital-age copyright law among people who will apply it creatively in their own circles and work. Unlike most MOOCs, CopyrightX runs simultaneously with the version of the course that Fisher teaches at the law school. This lets him link the two communities. Students in his law-school course, and alumni of it, volunteered to serve as "teaching assistants" for the online students. He divided the five hundred online students among these volunteers. Each week, the law-school class has two Socratic sessions on campus. The online students, meanwhile, have "sections" on the Web, taught by the teaching assistants. Every other week, the whole group convenes, in person or remotely, for an evening session at the law school. Artists, writers, and other copyright holders visit and speak about their legal concerns. The teaching assistants are in the room, but also online with their Web students, who are watching the event through a Webcast. "The teaching fellow is monitoring this discussion, participating in it, and then forwarding questions into the room," Fisher said. "So in the room there are two screens: one screening questions from the Harvard Law School students, and the other featuring the questions that are curated by the teaching fellows. And we oscillate the discussion between them." As the wheels of CopyrightX begin to turn, the course tries to deliver on all promises of online education: it proliferates useful knowledge beyond Harvard, it lets students learn by teaching, and it enriches the classroom environment by giving more time to discussion of hard problems. It also is not massive, open, or entirely online. "This is an old idea—it's basically the way seminars have been run for centuries," Fisher said. "But it remains a good one." |

| Posted: 17 May 2013 07:45 AM PDT Don Vito肯定是迄今为止西湖音乐节请的最另类的乐队。但且慢,另类这个词早就被用滥了,"另类摇滚"已经变得像一块干净的抹布,我不是想说Don Vito像一块肮脏的抹布,不,他们就是尘埃本身,是宇宙尘埃本身,最终生成了雷电。 Don Vito还是摇滚乐吗?当然,吉他贝司鼓三件套,只不过他们完全打破了摇滚歌曲的基本套路,首先,器乐(以及自制的效果器)拧成无序的狰狞的一团,然后,他们不唱歌,只一个劲尖叫。他们把自己的音乐命名为"超级无秩序动感器乐"(hyper kinetic instrumental noise tohubohu)"。乐队的名字来自于电影《教父》中由马龙·白兰度饰演的老教父科利昂(Don Vito Corleone),教父,就是打破既有的秩序,或在没有秩序的世界重建秩序,对他们来说:混沌就是秩序,混乱就是秩序。他们出过四张专辑,最出名的是一张精选黑胶,但请记住这样的乐队现场永远比录音牛逼,观众的尖叫,喷洒到他们身上的啤酒,乃至户外头顶的雨水,都可以成为他们演出的一部分,成为他们音乐的助燃剂。对他们来说,音乐不是一个容器,而是容器之外的四处流溢。但是他们的混沌不是盲目,他们的混乱不是无序,越是混沌和混乱,越需要高度的默契和控制力,他们现场有很多即兴,但依旧植根于既有的动机,然后加以粉碎,聚合,再粉碎,再聚合...... Don Vito狂躁的另一面其实是洁癖——-尽可能地清除掉摇滚乐的杂质:滥情,煽情,陈词滥调。他们的音乐当然来源于朋克和硬核,尤其是碾核。然而,很多朋克千篇一律的口号和脏话听上去就像"今天天气哈哈哈"一样,很多碾核故作丧尸腔调装神弄鬼的风格一旦程式化了,也变得比唱诗班还无聊——没错,这就是为什么连碾核的祖师死亡汽油弹(Napalm Death)如今听上去都有点像乖乖虎,但是死亡汽油弹当年曾经启发了约翰佐恩(John Zorn)做了伟大的painkiller,而Don Vito师承的应该更多的是这种介乎碾核和自由爵士之间的音乐,以及无浪潮(no wave )————他们确实会令人想到那些日本无浪潮噪音乐队,比如Boredoms和Ruins。 2009年,我在北京D22酒吧看过Don Vito和法国乐队LE SINGE BLANC的演出,那是我那一年看过的最棒的摇滚现场。Don Vito2005年成立于莱比锡,而我2006年去过这座巴赫之城。我热爱巴赫,也热爱Don Vito,对我来说二者并不矛盾,我也曾经喜欢德国战车乐队,但如今再看他们演出,我感觉像他们就像一个活蹦乱跳的迪斯尼马戏团。而Don Vito可以说就是战车的对立面,他们尽可能地把摇滚乐华而不实的部分清除掉,只留下原始的能量,原始的噪音,原始的尖叫——但可不是那种加了大量效果的死亡金属式的嘶吼,那种刻意卖骚的一招一式有时候会让我觉得像看一部性爱姿势速成指南一样腻味,一种貌似性感的刻板。这就是为什么don vito有时候干脆就不用麦克风,只用纯粹的肉嗓肉搏。一架高速运转的宇宙噪音永动机,哦不,是奋不顾身向死神冲决而去,每首曲子一般只有一分多钟,短的甚至只有几十秒,但他们演四十五分钟相当于别的乐队演三四个小时,因为那是用死亡的加速度在演——与其说是演奏,还不如说是在引爆,鼓手会打到打不动为止,这是远比死亡金属更死亡的音乐。 Don Vito2008年在挪威参加了By Alarm音乐节,当时奥斯陆还有另一个大型的商业音乐节,乐队同时收到了这两个音乐节的邀请,而他们所选择的"By Alarm"恰好是一个抵制后者的另类独立音乐节。西湖音乐节既邀请了选秀歌手又邀请了Don Vito,这是一种有中国特色的包容。而Don Vito也是平等而包容的———他们将像铲车一样挖掘每个人身上潜藏的黑暗莫测的能量,哪怕你并不是摇滚乐迷。

(刊于都市快报)  青春就应该这样绽放 游戏测试:三国时期谁是你最好的兄弟!! 你不得不信的星座秘密 青春就应该这样绽放 游戏测试:三国时期谁是你最好的兄弟!! 你不得不信的星座秘密 |

| Posted: 17 May 2013 06:45 AM PDT 起初,蕭神創造是非! 後記, 5月3日 後記2, 5月17日 劉嘉鴻突然提出另一個方案和先前說法相反,但又說執委未作決定云云,我會說討論這種倒退的方案,就是劉嘉鴻製造混亂!劉的突然考慮那個「需要選舉」的提名委員會,實在是耐人尋味及令人疑慮。 蕭神第二擊好像出現了! |

| Posted: 17 May 2013 06:09 AM PDT 我是明愛專上學院的學生,在校差不多兩年的時間,今天竟在一日內發生了三件作為明愛學生的我感到羞恥的事,我對校方作出的決定表示憤怒及痛心,希望校方能對著所有學生作一個交代以及對被事件受阻及侮辱的學生道歉。 事源,校方為了慶祝明愛成立60 周年,於2013年5月15日至18日借出了場地舉辦國際會議。校方為了攀龍附鳳,先把我們唯一的民主牆給河蟹了。 民主牆之河蟹圖 接著,我們偉大的特首於5月16日舉辦的會議,擔當主禮嘉賓,當他到達現場時,遇上了一群正想和平遞交請願信的示威學生(當中包括數名明愛學生)。雖然校方沒有像城大般出動孔武有力的彪形大漢把學生抬走,但是校方竟把責任推卸在學生身上,說成是學生在校園內搗亂,邀請警方介入,造成警員對學生叉頸,熊抱,推撞,踩踏,拖行等情況,最後學生被警方以非法集會,擾亂公眾秩序等罪名,要求登記身份資料,同時有可能對學生作出檢控。我對校方邀請警方介入,驅散自己的學生感到憤怒! 最可悲的是,當梁振英離開不久,校方在沒有知會學生的情況下,以特殊情況,封校等多種不同的理由,拒絕同學進入校園,即使是持有學生證,趕往考試以及交功課的同學都不能進入,某某副校長(紅圈者)更出言不遜,謾罵學生「講大話」,說成學生因為要進入校園而「講大話」,校園本是學生與校方共同擁有的地方,進入校園是學生的權利,即使在甚麼的情況下,校方不應封鎖校園,不讓同學進入,你們所聘用的保安,是用來保護學生及所有教職員的安全,並不是你們用作抵擋學生的工具。 最後,我覺得最可恥的,並不是校方怎樣對代學生,而是它們怎樣對代長者。下午,一班長者到了學校門外等待司長林鄭月娥,本打算和平遞交請願信,然後和平散去,誰不知,司長竟沒有兌現承諾,她的司機開著房車,長驅直進經過閘門,駛進了校園,漠視了一班示威者的訴求(當中亦包括明愛的同學),司長的房車進入校園,同學窮追不捨,只希望能夠把請願信交給司長,但是同學追到二樓時,遭受保安粗暴對代,以口勸籲學生不要衝撞,但雙手卻不斷推撞學生(學生是沒有推撞保安或其他人士,只是沿途呼叫口號),最後,司長安然進入會場。不久工作人員走來傳達訊息,司長願意接收各團體的請願信,之後團體代表魚貫排列等代司長收信,但百般不得其解,為何團體代表已經魚貫排列乖乖的等待司長,學校保安還要築起人鏈抵擋?難道我們這一小撮人能在被大量警方及保安的看守下,會傷害司長嗎? 就著以上幾點,希望校方能夠作出回應: |

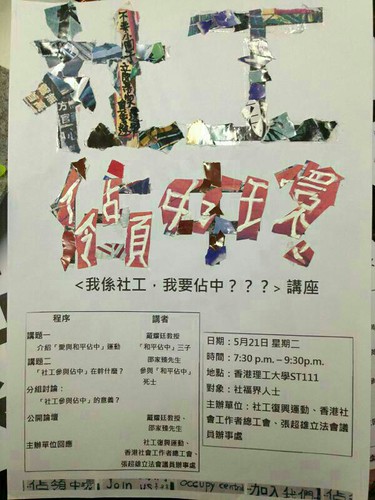

| Posted: 17 May 2013 05:01 AM PDT D-Day學會對話 (獨媒特約報導)談到6月9日舉行的商討日(Deliberation Day,D-Day),阿臻相當雀躍,並認為較佔領更重要,因為這是改變政治生態的契機:「我認為D-Day的吸引力,是如何實踐審議民主,如何跟香港政治碰撞。香港的政治太多assertion,一句到底,甚少deliberation,尤其民粹主義當道。但我們要嘗試審議公共事務。我覺得deliberation應譯為審議。要有information,tenderness,patience。我會聆聽你說,明白你的說話,然後回應你,而非一句「hi auntie」。用最簡單的概念,就是對話,而非獨白。Assertion是獨白。我也不熟悉。」 「對話是讓人退一步,而非進一步。對話不是遊說,對話是修正自己立場。尤其是在首次商討日,每個人也有很強的個人看法。審議民主是顛覆代議民主。不論任何背景,參與者也是常人。如果陳方安生也參加商討日,我很希望她能跟順嫂一起討論、辯論。」 審議也有譜 那邊廂,如果有人很想從根本討論佔領行動,又如何?「有人從最根本的概念討論,而且很有耐性,例如好像2011年的佔領中環,討論甚麼是鈔票。今次商討日不同,是有很清晰的框架,即是2017年的特首選舉方案,不容否定。這明顯有時間期限,不容參與者mingle。第二,佔領中環也有最基本的共識,例如非暴力。」 正文:【佔中十子專訪】邵家臻:佔中豈能缺社工 介紹:邵家臻,任教香港浸會大學社工系,亦為青年研究實踐中心副主任。社工畢業二十年,唸大學時開始參與社福界的運動,後來涉足青年、政治、社會政策、文化研究,等等。經常亮相亮聲,還教大家性教育是咁的,但甚少走到抗爭前列線,多數會搞聯署、論述之類。他說反國民教育運動是第一遍,成為佔中死士是第二遍。 採訪、撰文:autumnyu、易汶健 |

| Posted: 17 May 2013 04:57 AM PDT (獨媒特約報導)先有三位發起人,再來十位死士,佔領中環行動有意捲入更多群體。社工老師邵家臻(阿臻)代表界別,本來沒有甚麼奇怪,反正他經常參與社會福利界運動,近年不時評論文化現象。奇怪之處,反而是他願意成為死士的原因:「我想重燃社工本來就有的抗爭精神。」 社工不能再缺席 不能再漠然 他到記者會那天才知道那十位死士是誰,之前也不認識他們。「這些江湖大事,很難仔細交代,行動靠信字。」他說。 香港有15,790名註冊社工,為何說沒有人?阿臻說了社工孤身作戰,以及恐懼共產黨是主要原因,抑壓了社工的抗爭精神:「過往十幾年越來越『淆底』,短期合約,機構行事行政化,只求執行不求創作,去技術化,缺少聯席之類的業界合作,助長『淆底』,come out要自己付代價,沒有人幫助。」 「社工害怕共產黨,因為對象不是香港政府,bargain對手是中國政府。議題不是福利政策,而是憲政。」 當成為死士後,同行反應如何?「第一個反應是來自教師同事。他在遠處見到我,微笑問:「(警察)捉左你未?」我說:「落堂先!」。第二個反應來自認識的人,他說會買一些豬肉乾和燒仙草給我,跟我打氣。」 來自同行的反應小。五一遊行,有兩位同行走過來,一位問:「咁勇呀?」另一位問:「做左死士呀?」還有一位,在學校碰到,跟我握手,說很尊敬我。學生私底下有討論,是好奇或關心為主,暫時沒有商討配合行動。 阿臻補了一句:「我不是記性好,而是經歷少。」社工也會參與社會行動,但以個人身份居多,較少用社工身份,或者集體用社工身份。結果,有一段很長的時間,社工界很「離地」,在多次社會和基層運動中缺席。最近的一兩次,大抵是抗議大澳社工被調職的河蟹事件,以及反國教運動。 當然,社工界和其他界別共同面對採取公民抗命的難題:「後果是坐牢,代價很具體。被捕,自首,抗辯,坐牢,很具體,不可能逃脫。之後能否再做社工呢,這些問題很重。衝閘、糊椒噴霧也見過,坐牢是out of imagination。社工界要很多思考。」 以磚自喻,阿臻認為自己粗糙、粗魯,期望自己行動可以引起社工界的迴響:「我最想引來的是社工界的抗爭精神,社工不抗爭的就不是社工,對不公義、命運和制度的抗爭。」 「社工面對恐懼,大部份也不至於背叛,或者轉投建制陣營,但也不會直接抗爭,所以選擇漠然。我現在要處理社工界的漠然……行內很多人看著我長大,我在青協工作,一個相當大的機構,也是相當保守的機構。二十年來也有發表意見,我第一本書,前輩贊助我自資出版。跟我同屆的社工學生,不少也當上機構management。今天我出來,難道看著我長大的人也漠然?」 出得黎行,今鋪要還 「我信耶穌,雖然我不信基督教。有時是有東西替我安排。我沒有買樓,沒有女友,沒有結婚,沒有兒女。沒有很多包袱,為何不去?剛巧學校跟我續約,還跨越這幾年,於是不久就come out了。整件事情配合相當巧妙,掛慮少了……以前有一些賬單人家替我『找數』,今次要自己來。」 阿臻不諱言,教席和老媽是最大的顧慮。「有人一定會質疑,我比他容易走出來。我反問,為何我會比你容易?我有不少established的東西也可能失去,包括教席。我媽也有囉唆。」 社工的三大任務 說服基層,社工有能力,也有責任 他預料同學會跟他說這番話,但來得早,來得急切。他們知道佔領中環,但未必支持。這是必然,又是無奈:「這個問題是well-addressed……暫時佔中運動很難走入基層。阿戴的血和尿也有法律,有程序。任何時候也說程序、邏輯。這沒辦法,誰人kick off,運動就有誰人的影子。找杜汶澤開始,也有杜汶澤影子。再者,商討日和佔領日也要報名、宣誓,讓人感覺這場是學術實驗。重點是淡化個別人士的色彩。」他稱運動成員正想辦法把訊息傳入大眾。 個人關係阻礙阿臻說服身邊的基層同學。也許,運動的一個成功指標,是其他社工能夠令他們支持佔中。5月21日,社工界在理工大學將舉行第一場公民抗命講座,他鼓勵大家站出來,配合實際行動,擔當更多的崗位和工作。 抱歉,不打算在佔中改變資本主義 不過,阿臻不會要求運動帶向改變資本主義:「這刻我是處理人對政治的恐懼,冷漠。」他自稱他是cultural left,改革目標可以多元化,「抗爭精神就是大家可以抗中央、抗機構、抗社署……在我看來,中環只是中途站,不是終結。」 佔領中環的政治和個人後果,其實不只是社工,大部份支持者也是out of imagination,不少社工界的憂慮,也是其他行業和群體的憂慮。只是說,社會工作強調倡議改變,不論是個人、家庭、社會、以至宏觀制度,提升總體福祉。如果連業界工作者也不站出來,很難說服其他行業走出來。又或者說,如果其他行業走出來,而業界不站出來,社工很難再捍衛基本價值觀及信念。 後記:笑口盈盈地憤怒 阿臻對此事的第一反應是憤怒:「是恃強凌弱,我覺得他們很卑劣、無恥,不敢搞佔中三子,不敢搞佔中死士,而我們必須要高調反應。」 採訪、撰文:autumnyu、易汶健 |

| Posted: 17 May 2013 04:37 AM PDT xxxx xxxx 但有時看到左派是指支持社會主義及共產主義,那我又混亂了~ Jonathan C K Ho 今日的中共已放棄公有制,也沒有堅持社會財富公平再分配,即這不再是左派了。左派是既有建制的剝削性作出反對,右派就是要保持現狀不變。香港教會是右派,是因基要主義的根太深,喜歡把基督信仰去政治化,但「去政治化」本身就是一種政治手段,不提政治便有利保持政治現狀。 今日的中共是法西斯右派,是以幾千萬組成的政黨獨裁統治中國13億人,比例上少於人口十分一,而真正有權有錢的是一二千個家庭,這種獨裁特權體制本身就是和希特拉的國家社會主義即納粹黨相同,所以叫中共是法西斯,是最恰當的形容詞。 xxxx 那民建聯這些可算是名字上的「左派」,實為「右派」呢? Jonathan C K Ho 民建聯是右,不過又是67年暴動那時香港慣用「左仔」去說民建聯那群人。現在,民建聯個個是富翁,港共政府不斷搞東西開位送錢給他們,他們的人能做政治助理,個個有十萬人工。 朱耀明是司徒華的跟班,說來說去都是64及支聯會,基本上他是民主黨的同盟。用陳雲的說法,他是離地中產,有美國護照,戴耀庭搞佔中,他便撲出來佔領光環,即是出風頭。到香港大亂,及佔中失敗,他便會去美國退休。如果朱肯放棄美國國籍,我才會放棄上述的判斷,否則,他只是投機份子,即是「扮民主派」。其實,整個民主黨都是這類人,人人有外國護照,說說人權民主容易,有事便棄港於不顧。用左或右,皆不能去形容朱,因我說朱是右,別人總會說他示過威爭取過東區醫院云云,朱可算是不投入的左吧!到關鍵時刻,他便會怕死退縮,這是司徒華一代及其徒子徒孫的民主性格了! xxxx 感謝~讓我解開了一些謎團~您會怎樣理解「什麼是政治」呢? Jonathan C K Ho 政治?其實,政治和宗教本是一家。政治內有信念,信念引發政策,再下一層有其他細微運作。宗教也是有信念,信念引發教義,再下一層便是實務守則。政治就是權力的結構與運作,這是每個有人的地方也會有政治。就算,家裡只有兩公婆,兩個人對資源運用也會有不同的優先次序,兩個人也可能籍不同的策略去說服對方跟隨自己想優先購買的東西。而經濟學是純理性去分析怎樣使用資源,而政治是用理性的說詞或談判或利益交換去爭取對自己有利的資源運用。不說兩公婆,就說一對同性朋友,兩個人離與聚也可能有計算,如對方擅長某些知識,多親近會對自己有利,又或者對方和自己有相同嗜好,一起玩,便參與該嗜好時會有人陪,會玩得開心些。這是利益計算的一部份,這便算是政治了。兩個人都可以有政治,即任何群體包括堂會也會有政治。而生活上的各方各面,香港政府也會有某些的參與,如政策及法例的制定,這是會受當局者的政治取向所影響,根本衣食住行也必然有一些背後的政治因素所支配,即「去政治化」的教會教導只是一個神話。基要主義在二十年代經王明道倪柝聲等傳入中國建立新教堂會;但這一套在神學上已走入絕境,因為現代人面對社會的急速改變,外面的政、經及文化趨勢必然會影響堂會,當我們仍用過時的神學去處理萬變的社會,這注定和年青被壓迫的一代割裂出去。年青的一代是較上一代聰明,卻較上一代缺少機會,他們看透政教分離那套「去政治化」的奸謀,見到堂會只是當權者的附庸,去勸人不理政治,結果就是年青人不回教會,或又或者是溝到女就不回教會。牧養是要道成肉身,走入人群,和他們同呼吸,而「去政治化」或政教分離的說法就是牧者走入人群的主要攔阻。 xxxx 再請教一下我同意根本只要有兩個人都可以有政治,那些說去政治化的人,本身就政治化了一件事。其實什麼都是政治,那其實根本就沒可能沒有政治呢? Jonathan C K Ho 我不想把所有事也說成政治,我只能肯定兩個人之間會有政治。人與人之間可以是單純因我愛你,你喜歡吃什麼,我便讓你作主,無論誰請客也好。愛的動機也可以產生政治,因我想我的兒子肯聽我那對他有益的勸告(如學習溫柔待人,日後與人相處可以順利些),可能用一些策略一些利益交換去爭取他給我時間來聽我的勸告。我也不是專家,也不需要太理論化。我是相信人與人是可以有不計算利益,純然是愛與信任及接納的交住。 xxxx 感謝指教^^ |

| Posted: 17 May 2013 04:29 AM PDT xxxx 弟兄 xxxx 但有時看到左派是指支持社會主義及共產主義,那我又混亂了~ Jonathan C K Ho 今日的中共已放棄公有制,也沒有堅持社會財富公平再分配,即這不再是左派了。左派是對既有建制的剝削性作出反對,右派就是要保持現狀不變。香港教會是右派,是因基要主義的根太深,喜歡把基督信仰去政治化,但「去政治化」本身就是一種政治手段,不提政治便有利保持政治現狀。 今日的中共是法西斯右派,是以幾千萬人組成的政黨獨裁統治中國13億人,比例上少於人口十分一,而真正有權有錢的是一二千個家庭,這種獨裁特權體制本身就是和希特拉的國家社會主義即納粹黨相同,所以叫中共是法西斯,是最恰當的形容詞。 中共的左只是旗號,無任何內涵。若回到1949年以前,中共是要推翻國民黨四大家族的貪污獨裁,那時稱中共是左,是對的。可是六十多年過去,中共比當年4大家族更為貪腐,貪得更廣更深,現在的中共只可以稱為右,但中共用「左」字多年,「左」在中國內地便變成支持中共專政的術語了。 xxxx 那民建聯這些可算是名字上的「左派」,實為「右派」呢? Jonathan C K Ho 民建聯是右,不過又是67年暴動那時香港慣用「左仔」去說民建聯那群人。現在,民建聯個個是富翁,港共政府不斷搞東西開位送錢給他們,他們的人能做政治助理,個個有十萬人工。 朱耀明是司徒華的跟班,說來說去都是64及支聯會,基本上他是民主黨的同盟。用陳雲的說法,他是離地中產,有美國護照,戴耀庭搞佔中,他便撲出來佔領光環,即是出風頭。到香港大亂,及佔中失敗,他便會去美國退休。如果朱肯放棄美國國籍,我才會放棄上述的判斷,否則,他只是投機份子,即是「扮民主派」。其實,整個民主黨都是這類人,人人有外國護照,說說人權民主容易,有事便棄港於不顧。用左或右,皆不能去形容朱,因我說朱是右,別人總會說他示過威爭取過東區醫院云云,朱可算是不投入的左吧!到關鍵時刻,他便會怕死退縮,這是司徒華一代及其徒子徒孫的民主性格了! xxxx 感謝~讓我解開了一些謎團~您會怎樣理解「什麼是政治」呢? Jonathan C K Ho 政治?其實,政治和宗教本是一家。政治內有信念,信念引發政策,再下一層有其他細微運作。宗教也是有信念,信念引發教義,再下一層便是實務守則。政治就是權力的結構與運作,這是每個有人的地方也會有政治。就算,家裡只有兩公婆,兩個人對資源運用也會有不同的優先次序,兩個人也可能籍不同的策略去說服對方跟隨自己想優先購買的東西。而經濟學是純理性去分析怎樣使用資源,而政治是用理性的說詞或談判或利益交換去爭取對自己有利的資源運用。不說兩公婆,就說一對同性朋友,兩個人離與聚也可能有計算,如對方擅長某些知識,多親近會對自己有利,又或者對方和自己有相同嗜好,一起玩,便參與該嗜好時會有人陪,會玩得開心些。這是利益計算的一部份,這便算是政治了。兩個人都可以有政治,即任何群體包括堂會也會有政治。而生活上的各方各面,香港政府也會有某些的參與,如政策及法例的制定,這是會受當局者的政治取向所影響,根本衣食住行也必然有一些背後的政治因素所支配,即去政治化的教會教導只是一個神話。基要主義在二十年代經王明道倪柝聲等傳入中國建立新教堂會。但這一套在神學上已走入絕境,因為現代人面對社會的急速改變,外面的政經及文化趨勢必然會影響堂會,當我們仍用過時的神學去處理萬變的社會,這注定和年青被壓迫的一代割裂出去。年青的一代是較上一代聰明,卻較上一代少一點機會,他們看透政教分離那套去政治化的奸謀,見到堂會只是當權者的附庸,去勸人不理政治,結果就是年青人不回教會,或又或者是溝到女就不回教會。牧養是要道成肉身,走入人群,和他們同呼吸,而去政治化的政教分離說法就是牧者走入人群的主要攔阻。 xxxx 再請教一下我同意根本只要有兩個人都可以有政治,那些說去政治化的人,本身就政治化了一件事。其實什麼都是政治,那其實根本就沒可能沒有政治呢? Jonathan C K Ho 我不想把所有事也說成政治,我只能肯定兩個人之間會有政治。人與人之間可以是單純因我愛你,你喜歡吃什麼,我便讓你作主,無論誰請客也好。愛的動機也可以產生政治,因我想我的兒子肯聽我那對他有益的勸告(如學習溫柔待人,日後與人相處可以順利些),可能用一些策略一些利益交換去爭取他給我時間來聽我的勸告。我也不是專家,也不需要太理論化。我是相信人與人是可以有不計算利益,純然是愛與信任及接納的交住。 xxxx 感謝指教^^ |

| Posted: 17 May 2013 03:31 AM PDT (獨媒特約報導)隨著年月過去,各方對於八九年在北京天安門發生的六四屠城事件作出質疑的聲音日益增多,有人懷疑當年學生先使用暴力或認為他們不懂進退,遂導致政府的武力鎮壓。有聲音則指摘當年的學生領袖爭權奪利,事件結束後逃亡外地之餘;生活日漸腐化,質疑他們並不是真心愛國和追求民主。新亞書院學生會在昨日(5月16日)舉行「香港傳媒與六四事件」的新亞沙龍,邀請了四位資深傳媒工作者: 程翔、區家麟、謝志峰及柳俊江,就以上議題作出討論及分享。 圖:謝志峰是當時留守至最後的其中一位記者 何謂中立報導? 港媒自我審查嚴重 他補充,連敢死隊的敢死方法也是絕對的非暴力,而非印象中玉石俱焚的敢死。「敢死隊踩單車去軍車所在地,向軍人送水和麵包,說服他們學生所想爭取的價值,另有人睡在軍車的車輪底。」謝繼續指出,學生領袖當時已極力維持和平抗爭。「他們廣播叫拿了軍隊槍支的人要送槍去中央銷毀。」但他認為難以控制來自兩岸三地的大群民眾,而組織鬆散亦是無可厚非,中共才需為屠城負上最大責任。 「權利爭奪(學生之間的)只係爭咪講野,講得好群眾會拍手,另一個就會上去爭咪講。有北京學生又有唔同地方來的學生,都不知離開還是向前好;政府知悉的情況最多,有民間組織、警察、情報系統等,所以政府責任最大。」而學生領袖相繼逃亡國外並不等於他們當時的行為不是出於道德立場。「愛國唔等於傻到等給槍殺吧,學生多來自北大及清大,前途可說是一片光明,他們大多基於道德及人權才選擇去絕食。」 前無綫電視新聞記者區家麟亦回憶說,當時整個無線新聞部人員全都「發狂」;他們讀著通訊社傳來的外電消息,哭著問為什麼會向手無寸鐵的人開槍。當日的經歷讓區家麟認為報道不公義的事情是記者的任務,但香港傳媒日漸漠視六四;甚至自恃不偏不倚「中立客觀」地報道六四,才導致新一代對六四歷史感到模糊。 區更認為,此舉最終只會埋沒六四真相,落得與日前被一中學生說成尊重和包容的五四精神同一下場。「在大是大非幾乎沒可能中立,不偏不倚(報道方法)只是為了尋找真相。」同是前無綫電視新聞記者的柳俊江亦認為,媒體甚至社會已默默接納「假中立」,有實據支持仍拒絕表示立場。「在六四20週年特輯中,主流媒體全都含糊其辭,講幾個香港人每年去下維園,組織研討會等等,就當講左。 Now TV講坦克,大家已經覺得好大膽。」柳批評行內自我審查情況嚴重,記者亦會揣測高層會否對付自己。這最終從而抹殺港人應有的認知權;區家麟回應指,現在香港媒體變有些做法更不如內地某些媒體,內地某些媒體會嘗試擦邊球,本地媒體則主動玩閃避球,積極不主動去調查政府做法及發掘新視點。 中國現再陷廿四年前困境 現實縱氣餒但仍感樂觀 柳俊江指現況雖令人灰心,但仍有一綫生機。「內地來了個教育領導高層,他曾留學海外,他認為中國建立唔到素質教育是因為不會教是非對錯之分。這群有力量的人進入了政體核心,將來會很大幫助。」謝志峰亦樂觀地表示,仍有信心將來內地不會缺乏平反的力量。「這並非中國人劣根性,我們可以為中國政府感到失望,但唔可以忘記有十三億民眾;民眾會跟香港記者講好多野,公安都會幫手,叫記者過帶。」 中港關係不可割裂 港人肩負平反六四重任 而區與程亦認同中國與香港不論文化上或是現實上,都不能割裂。現實上大陸的制度影響香港甚多,不過程認為香港制度展現的優勢亦能反饋中國,不可低估香港的作用,認為只要香港人做好每一件事就可以成為榜樣。「我曾問過一位雙非媽媽為何來港,我以為她會如中介般回答居港權和福利,但她卻說在香港長大的孩子會學懂規矩。」因此,程認為香港人肩膊上有重大的歷史責任,去推動平反六四,從而推動國情的改變。 柳俊江亦表示,香港應在中國事務上扮演更重要的角色,認為港人不能抱著事不關己的心態而拒絕。「對於某啲網上言論,聆聽後覺反感,因為言論屬功利主義、自我中心,並無為道德而犧牲的想法。」 編輯:麥馬高 |

| Posted: 17 May 2013 01:30 AM PDT |

| Posted: 17 May 2013 01:05 AM PDT 《凤凰周刊》2013年12期 《凤凰周刊》 朱艺 2013年3月,在全国两会上,全国人大代表、福建省漳州市副市长赵静向大会提交了《关于支持漳州成为赴台个人游......>>点击查看新浪博客原文  青春就应该这样绽放 游戏测试:三国时期谁是你最好的兄弟!! 你不得不信的星座秘密 青春就应该这样绽放 游戏测试:三国时期谁是你最好的兄弟!! 你不得不信的星座秘密 |